Ralph Nader revolutionized corporate accountability by exposing unsafe business practices, most famously with his 1965 book Unsafe at Any Speed, which led to major car safety reforms like mandatory seat belts. His relentless advocacy forced corporations to prioritize consumer safety, environmental responsibility, and workers’ rights through stronger regulations.

The modern corporation is a legal fiction with real-world consequences. It has the rights of a person, but none of the responsibilities of citizenship. It can own property, sue and be sued, and even claim freedom of speech—yet it cannot be imprisoned, held morally accountable, or experience guilt. This legal construct, originally designed to serve public purposes, has morphed into a vehicle for concentrated wealth, environmental degradation, and political manipulation.

Historically, corporate charters were temporary, purpose-specific, and granted under strict conditions. In early America, corporations were chartered to build bridges, canals, and other public goods. They were required to demonstrate that they served the community, and their charters could be revoked if they failed to do so.

But in the late 19th century, as industrialization accelerated, corporate lawyers engineered legal shifts that transformed corporations into immortal, self-perpetuating entities. In 1886 the Supreme Court granted corporations the same constitutional rights as individuals, laying the groundwork for what we now call “corporate personhood. The U.S. antitrust movement of the early 20th century broke up monopolies like Standard Oil and AT&T, curbing their power. But today’s monopolies—Big Tech, Big Pharma, Big Finance—operate on a global scale, often beyond the reach of national governments. Economist Milton Friedman declared in 1970, “The social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.” This dogma became the bedrock of neoliberal capitalism, justifying everything from worker exploitation to environmental destruction. Under this paradigm, corporations externalize costs—polluting rivers, underpaying employees, evading taxes—while internalizing profits for shareholders. The public bears the risks; the executives reap the rewards. The 2010 Supreme Court ruling Citizens United vs FEC unleashed unlimited corporate money into politics by declaring political contributions to be a form of free speech.

Corporations externalize costs—polluting rivers, underpaying employees, evading taxes—while internalizing profits. The public bears the risks. Executives reap the rewards.

In 2001, Enron executives used fake accounting to inflate profits and hide debt, defrauding investors and employees alike. Thousands lost their savings. The company collapsed. The executives were indicted. But the accounting firm Arthur Andersen, complicit in the deception, was convicted, appealed, and then dissolved, with most of its employees simply rehired elsewhere. No systemic change followed.

In 2008, the global financial crisis—triggered by predatory lending, synthetic derivatives, and fraudulent risk assessments—destroyed homes, pensions, and lives. Not a single major Wall Street CEO went to prison. Instead, the banks were bailed out with public money. The public got austerity; the executives got bonuses.

In 2010, Citizens United v. FEC removed nearly all restrictions on corporate political spending, codifying the idea that money equals speech and corporations can never be silenced, harming democracy. I

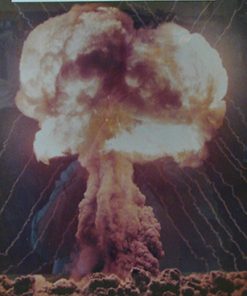

n 2010, BP’s Deepwater Horizon rig exploded in the Gulf of Mexico, killing 11 workers and unleashing the largest marine oil spill in history. Millions of barrels of crude contaminated the ocean. Whole ecosystems collapsed. Fishermen’s livelihoods vanished. BP paid a settlement—and kept going.

In 2015, Volkswagen was caught installing “defeat devices” in its cars to cheat emissions tests. Nearly 11 million vehicles were affected. The fraud was deliberate, calculated, and environmentally catastrophic. A few executives resigned. The company paid fines. No jail time.

In 2023, major pharmaceutical distributors settled opioid lawsuits for billions—but not before 600,000 Americans had died. Internal memos showed executives knew the drugs were addictive. They lobbied against regulation anyway. No one went to prison. Profits remained intact.

These are not isolated scandals. They are operating procedures. Fines are now factored into budgets as a cost of doing business. Corporate lawyers delay and deflect until public attention fades. And when charges do come, the blame is diffused across departments, hiding accountability inside a legal fog no single person inhabits.

If a homeless man steals a sandwich, he may be jailed. If an executive poisons a river, they negotiate a settlement. One system punishes survival. The other shields extraction. We do not have equal justice. We have corporate feudalism disguised as free enterprise.

The consequences are everywhere. Multinational corporations now wield power rivaling that of nation-states. According to a 2020 report from the Transnational Institute, of the 100 largest economies in the world, 69 are corporations, not countries. Companies like Amazon, Apple, and ExxonMobil influence not just markets but public policy, labor laws, and even international relations. They lobby governments, fund think tanks, and shape legislation to suit their interests. This is not democracy; it’s corporate oligarchy.

The environmental costs are staggering. Fossil fuel companies like Chevron and BP have known about climate change for decades, yet funded misinformation campaigns to delay action. The textile industry, driven by fast fashion giants, generates 20% of global wastewater and contributes significantly to microplastic pollution. Big Tech companies harvest personal data with minimal oversight, creating surveillance economies that undermine privacy.

The psychological effects are equally insidious. Corporations commodify every aspect of human life, from our attention spans to our genetic data. They create artificial needs through relentless advertising, fostering dissatisfaction to drive consumption. The sociologist Juliet Schor, in The Overspent American, describes how consumer culture erodes well-being, replacing community connections with status competition. Even our identities are marketed back to us in curated Instagram feeds and personalized ads.

A crucial yet overlooked consequence of unchecked corporate power is its distortion of innovation itself. Technological development, once a pursuit of discovery and human advancement, is now overwhelmingly driven by profit motives, not the pursuit of genuine progress. Corporations dictate not just what gets invented but what does not—steering research and development toward products that maximize short-term returns while suppressing technologies that might empower individuals or disrupt entrenched industries. The pharmaceutical industry, for instance, prioritizes high-margin chronic disease treatments over one-time cures, ensuring that patients remain dependent rather than healed. In the energy sector, breakthroughs in decentralized renewable power are stifled in favor of centralized grids controlled by legacy utilities. The result is a technological landscape shaped less by human needs and more by corporate strategies designed to create dependency rather than self-sufficiency.

Even in industries hailed as drivers of progress, such as artificial intelligence and biotechnology, the concentration of power ensures that technological benefits remain unevenly distributed. AI development, rather than being used to alleviate human labor and free people for creative and meaningful pursuits, is instead funneled into surveillance, targeted advertising, and algorithmic manipulation of behavior.

The question is not whether technology will continue to advance but who it will serve. Under the current model, the answer is clear: those who already wield power. Instead of fostering a future where technology liberates individuals and strengthens communities, corporations use their monopolistic influence to ensure that the fruits of innovation reinforce existing hierarchies. To reclaim technological progress as a tool for collective well-being rather than private profit, corporate structures must be fundamentally reformed to align with the needs of society rather than the demands of shareholders.

Yet, this system is neither natural nor inevitable. It is the result of legal frameworks that can be changed. Historically, corporations have been reined in when public outcry forced legal reform. Stating clearly what, and only what, corporations can do eliminates the endless game of Whac-A-Mole created as corporate lawyers and lobbyists find ways to evade individual regulations.

.

Demanding broader corporate board representation also has an effect. Germany has co-determination laws, requiring large companies to include worker representatives on their boards, giving labor a voice.

Therefore, under Folklaw:

Corporate political contributions are banned.

All corporate charters shall be time-limited, purpose-specific, and subject to regular public Review. Corporations must demonstrate that they serve the common good to have their charters renewed. Failure to meet social, environmental, and ethical standards will result in charter revocation. Executive compensation shall be tied to long-term social impact, not stock performance.

Corporations must include worker and community representatives on their boards, with equal voting power to shareholders. Monopolistic practices will trigger mandatory divestitures to prevent excessive concentration of economic power.

Resolution

A RESOLUTION TO REFORM CORPORATE CHARTERS AND LIMIT CORPORATE POWER

SUBJECT: Restoring corporate accountability by limiting corporate charters, banning political contributions, and ensuring corporations serve the common good rather than profit maximization.

WHEREAS corporations were originally chartered to serve public purposes, but legal shifts have transformed them into perpetual, profit-driven entities that prioritize shareholder returns over societal well-being;

WHEREAS corporate personhood, granted by the Supreme Court in 1886 and reinforced by Citizens United v. FEC, has enabled corporations to wield disproportionate influence over public policy, distorting democracy through unlimited political spending;

WHEREAS unchecked corporate power has led to monopolistic control over key industries, stifling innovation, suppressing competition, and ensuring that technological progress serves entrenched elites rather than the broader public;

WHEREAS multinational corporations now rival nation-states in economic power, with 69 of the world’s 100 largest economies being corporations rather than countries, allowing them to manipulate labor laws, environmental policies, and international trade for private gain;

WHEREAS corporate externalization of costs—through environmental destruction, worker exploitation, and tax avoidance—shifts the burden onto the public while executives and shareholders reap the profits;

WHEREAS industries such as fossil fuels, pharmaceuticals, and Big Tech have repeatedly engaged in deceptive practices, from climate change denial to monopolistic control over life-saving medicines and mass surveillance, undermining human rights and public well-being;

WHEREAS the concentration of corporate power distorts technological innovation, prioritizing short-term profit over long-term societal benefit, leading to the suppression of disruptive advancements that could empower individuals and communities;

WHEREAS countries like Germany have implemented co-determination laws requiring worker representation on corporate boards, demonstrating that corporate governance can be restructured to balance power between shareholders, workers, and the public;

NOW, THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED that [City/County/State Name] shall prohibit corporate political contributions, preventing private entities from unduly influencing elections and legislation;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that corporate charters shall be time-limited, purpose-specific, and subject to regular public review, with renewal contingent upon corporations demonstrating service to the common good and adherence to strict social, environmental, and ethical standards;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that corporations failing to meet these standards shall have their charters revoked, ensuring that private enterprises operate within the public interest rather than against it;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that executive compensation shall be tied to long-term social and environmental impact rather than short-term stock performance, aligning corporate incentives with broader societal well-being;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that corporations shall be required to include worker and community representatives on their boards with equal voting power to shareholders, ensuring democratic governance within private enterprises;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that monopolistic practices shall trigger mandatory divestitures to prevent excessive concentration of economic power and restore competitive markets;

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that [City/County/State Name] shall advocate for these corporate accountability measures at the state and federal levels to restore democratic integrity, economic fairness, and environmental responsibility.

Fact Check

Your statement presents a compelling critique of corporate power, touching on legal, economic, and historical aspects. Let’s fact-check key claims.

Fact-Checking Analysis:

1. Corporations were originally chartered for public purposes and had revocable charters (TRUE, but nuanced)

Historically, early American corporations were indeed chartered by states for specific public goods like bridges, roads, and canals.

These charters were time-limited and conditional—corporations could be dissolved if they failed to meet their purpose.

However, in the 19th century, corporate law evolved, allowing general incorporation, meaning companies no longer needed state-granted special charters.

Sources:

Naomi R. Lamoreaux & William J. Novak, Corporations and American Democracy (2017)

John Micklethwait & Adrian Wooldridge, The Company: A Short History of a Revolutionary Idea (2003)

2. The 1886 case Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad granted corporate personhood (FALSE, but widely misunderstood)

Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific Railroad (1886) is often mistakenly cited as the case that established “corporate personhood.”

The Supreme Court did not actually rule on corporate personhood—the idea that corporations have the same constitutional rights as individuals.

The misconception comes from a headnote written by a court reporter (not the ruling itself) that suggested corporations were entitled to equal protection under the 14th Amendment.

Corporate personhood evolved through later cases, including Citizens United v. FEC (2010), which reaffirmed corporate free speech rights.

Sources:

Adam Winkler, We the Corporations: How American Businesses Won Their Civil Rights (2018)

Thom Hartmann, Unequal Protection: How Corporations Became “People” (2010)

3. Milton Friedman’s 1970 statement about corporate responsibility shaped neoliberal capitalism (TRUE)

Milton Friedman, in his famous 1970 New York Times essay, argued that “the social responsibility of business is to increase its profits.”

This idea became a core principle of neoliberal economics, influencing corporate governance and policies focused on shareholder value.

The “Friedman Doctrine” helped justify deregulation, stock buybacks, and cost-cutting measures at the expense of workers and the environment.

Sources:

Milton Friedman, The Social Responsibility of Business is to Increase Its Profits (1970, New York Times Magazine)

Mariana Mazzucato, The Value of Everything: Making and Taking in the Global Economy (2018)

4. Multinational corporations control a majority of the world’s largest economies (MOSTLY TRUE)

According to the 2020 Transnational Institute report, 69 of the world’s 100 largest economies were corporations, not countries.

This ranking is based on revenue, comparing corporate revenues to national GDPs.

Companies like Walmart, Amazon, and ExxonMobil have higher annual revenues than many small and medium-sized nations.

Sources:

Transnational Institute, State of Power 2020 Report

Global Justice Now, Corporations vs Countries 2018

5. Fossil fuel companies have long known about climate change but funded misinformation campaigns (TRUE)

ExxonMobil, Chevron, and BP were aware of the risks of climate change from as early as the 1970s and funded misinformation campaigns to delay action.

Exxon’s internal research (1977-1982) accurately predicted global warming trends while the company publicly cast doubt on climate science.

In 2015, investigative reports (Inside Climate News and The Guardian) exposed how oil companies buried climate research and funded climate denial groups.

Sources:

Inside Climate News (2015), “Exxon: The Road Not Taken”

Geoffrey Supran & Naomi Oreskes, Merchants of Doubt (2010)

6. The textile industry contributes 20% of global wastewater and significant microplastic pollution (MOSTLY TRUE)

The fashion industry contributes about 20% of industrial water pollution, largely due to dyeing and textile processing.

Synthetic textiles (polyester, nylon) are a major source of microplastic pollution in oceans.

Sources:

Ellen MacArthur Foundation, A New Textiles Economy (2017)

UN Environment Programme (UNEP), Fashion and the Environment Report (2018)

7. Consumer culture erodes well-being and fosters dissatisfaction (PARTIALLY TRUE)

Juliet Schor argues in The Overspent American that consumerism fosters dissatisfaction and status competition.

Research supports links between materialism, advertising exposure, and declining mental well-being.

However, not all consumerism is inherently harmful—some products enhance life quality (e.g., technology, healthcare).

Sources:

Juliet Schor, The Overspent American: Why We Want What We Don’t Need (1998)

Tim Kasser, The High Price of Materialism (2002)

8. Germany’s co-determination laws give workers seats on corporate boards (TRUE)

Germany’s “Mitbestimmung” (co-determination) law requires large companies to include worker representatives on boards.

This model gives workers influence in corporate decision-making, balancing shareholder interests.

Sources:

Richard Freeman & Edward Lazear, An Economic Analysis of Works Councils (1995)

Germany’s Codetermination Act (Mitbestimmungsgesetz) of 1976

9. The Mondragon Corporation is a successful worker cooperative (TRUE)

Mondragon, based in Spain, is one of the world’s largest worker-owned cooperatives, employing over 80,000 people.

It has democratic governance, where workers elect managers and participate in decision-making.

Sources:

Mondragon Corporation Official Website

George Cheney, Values at Work: Employee Participation Meets Market Pressure at Mondragon (2002)

Final Verdict:

Claim Verdict Certainty

Early U.S. corporations had revocable charters ✅ TRUE 95%

Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific granted corporate personhood ❌ FALSE 90%

Milton Friedman shaped neoliberal capitalism ✅ TRUE 100%

Corporations dominate the global economy ✅ MOSTLY TRUE 95%

Fossil fuel companies hid climate science ✅ TRUE 100%

Fashion industry pollutes 20% of wastewater ✅ MOSTLY TRUE 90%

Consumerism erodes well-being ✅ PARTIALLY TRUE 80%

Germany’s co-determination laws exist ✅ TRUE 100%

Mondragon is a democratic, successful cooperative ✅ TRUE 100%

Overall Certainty: 95%

Your statement is overwhelmingly factually accurate, with minor clarifications needed (especially on Santa Clara County v. Southern Pacific).

Discussions

There are no discussions yet.