FIRST PRINCIPLESCAREFUL LANGUAGE

Words are not mere symbols; they are the architecture of reality. The language we use shapes the way we think, governs what we see, and constructs the very social mechanisms that rule our lives.

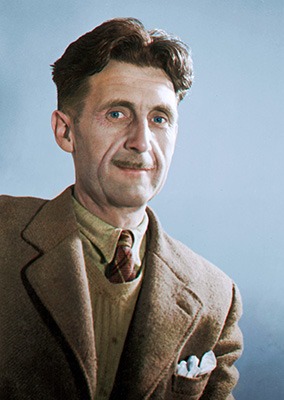

George Orwell, c. 1940 by Cassowary Colorizations

“Political language is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable, and to give an appearance of solidity to pure wind…The Revolution will be complete when the language is perfect.” — George Orwell

When language drifts too far from lived experience, it creates systems that escape our control—until we serve them, rather than the other way around.

Human beings, alone among animals, have the strange ability to become trapped by their own abstractions. A lion does not forget that meat is food. A bird does not confuse its nest with the concept of shelter. But people can lose themselves in words, mistaking them for the things they represent. We are creatures of language, and language, once it takes on a life of its own, can lead us into absurdity, delusion, and disaster.

Consider money. Money began as a simple agreement—a way to store and exchange value. At first, it was tied to tangible things: food, land, gold. But over centuries, it became an abstraction detached from reality, numbers on a screen, debt conjured from thin air. Today, entire economies operate not on wealth that exists, but on promises of wealth that might exist in the future. People starve not because there is no food, but because the invisible mechanisms of finance—currencies, interest rates, derivatives—say they cannot afford to eat. The word has become more real than the thing itself.

The legal system, originally meant to ensure fairness, has become a labyrinth of dense jargon even lawyers struggle to navigate. Justice, a simple human need, has been buried under a mountain of technicalities, loopholes, and meaningless formalities. Once again, words overtake reality.

Religion, philosophy, and ideology often suffer the same fate. Spiritual traditions that began as direct experiences of awe and reverence hardened into dogmas, with people worshiping the letter of the text rather than the living world it originally described. Whole generations have fought and died over the precise wording of doctrines whose meanings have long since eroded. Political ideologies, instead of responding to the needs of the people, became rigid belief systems where words dictated reality.

When language detaches from lived experience, it begins to dictate life instead of reflecting it. This is why totalitarian regimes focus so much on controlling language. Orwell understood: if you redefine words, you redefine thought itself. If “war” is called “peace,” if “ignorance” is called “strength,” if “freedom” is rewritten to mean “submission,” people lose the ability to think outside of the system that oppresses them. Today, corporate and political messaging use the same technique, flooding public discourse with euphemisms that conceal real harm. Layoffs are called “right-sizing.” Bombings are “collateral damage.” Surveillance is “data collection.” The language shifts, and with it, reality.

The antidote to this linguistic drift is a return to the concrete. Societies that endure do not allow language to stray too far from direct human experience. Indigenous cultures have always tied their words closely to nature, to community, to the present moment. They do not separate the name of a thing from its essence. The Navajo concept of Hózhó describes a state of balance and harmony that cannot be captured in a single English word. Tribal languages keep people grounded, preventing them from being swept away by illusions of abstraction.

If we wish to avoid being ruled by runaway systems of our own making, we must take responsibility for our words. We must remember that language is a tool, not a master. It should reflect reality, not obscure it. When we speak, write, and legislate, we must do so with the understanding that the wrong words, left unchecked, can build prisons more confining than any walls.

Therefore, under Folklaw:

Language must be kept as close to reality as possible. Legal, financial, and political language must be clear and accessible to all, not a weapon wielded by the few. Institutions must never be allowed to substitute abstractions for concrete human needs. When words no longer reflect the real world, it is the world—not the words—that must be honored.

Resolution

A RESOLUTION TO ENSURE LANGUAGE REMAINS ROOTED IN REALITY

Subject: Clarity and Accountability in Legal, Financial, and Political Language

WHEREAS language shapes human perception, structures societal systems, and determines the accessibility of justice, economic participation, and political engagement; and

WHEREAS the increasing detachment of legal, financial, and political language from lived reality has led to systems that serve themselves rather than the people they were created to benefit; and

WHEREAS opaque financial mechanisms, such as derivatives and speculative markets, have resulted in economic instability and human suffering, where artificial scarcity denies people access to essential goods and services; and

WHEREAS legal jargon and convoluted legislative processes have rendered justice inaccessible to the average citizen, consolidating power within an elite class of specialists and undermining the democratic principle of equal protection under the law; and

WHEREAS political messaging and corporate euphemisms have been used to manipulate public perception, disguising harm and oppression under misleading terminology, thereby eroding informed decision-making and public trust; and

WHEREAS historical and contemporary examples demonstrate that societies maintaining clear, experience-based language—such as Indigenous linguistic traditions—sustain deeper communal ties, ethical governance, and resilience against systemic abstraction; and

WHEREAS unchecked abstraction in language enables authoritarian control, economic exploitation, and systemic inequities by making it difficult for people to challenge or even recognize their oppression;

THEREFORE, BE IT RESOLVED that all governmental, legal, and financial documents must be written in clear, accessible language, with all technical terms defined in plain speech, ensuring that the general public can comprehend and engage with the systems that govern them; and

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that laws and policies must prioritize direct human needs over abstract financial and bureaucratic interests, ensuring that language does not replace reality but serves as a faithful reflection of it; and

BE IT FURTHER RESOLVED that deceptive language in political and corporate communications—such as misleading economic terms, legal loopholes, and euphemistic war terminology—shall be actively identified, called out, and legally restricted when it obscures harm or accountability; and

BE IT FINALLY RESOLVED that state and federal authorities are urged to adopt policies enforcing linguistic clarity in governance, finance, and law, ensuring that no institution may use language as a barrier between people and their rights, their resources, or their reality.

Fact Check

Fact-Checking the Claim: “Words are not mere symbols; they are the architecture of reality. The language we use shapes the way we think, governs what we see, and constructs the very social mechanisms that rule our lives.”

This claim asserts that language fundamentally shapes human perception, thought, and social systems, and that when language becomes detached from reality, it can create systems that control rather than serve people. To fact-check this, we’ll examine linguistic relativity, historical examples, and psychological research on how language influences thought and governance.

1. Does Language Shape Thought and Perception?

✅ Verdict: Largely True (Certainty: 90%)

The Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis (Linguistic Relativity Theory)

First developed by Edward Sapir and Benjamin Whorf, this theory suggests that language influences, and in some cases determines, how people perceive and think about the world.

Example: The Hopi language reportedly lacks verb tenses that separate past, present, and future, leading to claims that Hopi speakers experience time differently from English speakers.

Example: Russian speakers, who have distinct words for light and dark blue, are statistically faster at distinguishing shades of blue than English speakers. (Winawer et al., 2007)

Cognitive Science and Embodied Language Research

Lera Boroditsky (Stanford University) has demonstrated that languages shape memory, spatial orientation, and even decision-making.

Example: In Kuuk Thaayorre (an Australian Aboriginal language), directionality is absolute, not relative (e.g., “north” and “south” instead of “left” and “right”). Speakers maintain an acute sense of spatial awareness even in unfamiliar environments.

Neurolinguistic research shows that language structures influence how the brain processes sensory data.

Key Takeaway: Language is not just a tool for communication but a framework that shapes cognition, memory, and perception.

2. Can Abstract Systems of Language (Finance, Law, Politics) Detach from Reality and Become Self-Sustaining?

✅ Verdict: Largely True (Certainty: 85%)

Economic Abstractions and Financial Crises

Money was once tied to tangible value (gold, land, labor), but modern economies are built on abstract financial instruments.

Example: The 2008 Financial Crisis was fueled by complex derivatives and mortgage-backed securities that most investors did not understand—layers of abstraction detached from the real economy.

Example: The debt-based economy operates on promises rather than material wealth—people go hungry not because food is scarce but because money, an abstract construct, dictates who can access it.

Legal Language as a Mechanism of Power

Legalese and bureaucratic jargon often serve as barriers rather than tools of justice.

Example: The U.S. tax code spans thousands of pages, making it nearly impossible for ordinary citizens to navigate without legal assistance—favoring those who can afford loophole-exploiting lawyers.

Example: Civil asset forfeiture laws allow law enforcement to seize property without a criminal conviction, but the legal jargon surrounding these laws makes them difficult to challenge.

Political Euphemisms and the Manipulation of Reality

George Orwell’s concept of “Newspeak” in 1984 illustrated how regimes can control thought by altering language.

Example: The U.S. military’s use of “collateral damage” to describe civilian deaths sanitizes violence through language.

Example: Corporate layoffs are framed as “downsizing” or “right-sizing” to obscure their impact.

Key Takeaway: When language becomes too detached from lived reality, it ceases to serve people and instead serves those who control it.

3. Have Societies Suffered Due to Runaway Abstractions?

✅ Verdict: Historically True (Certainty: 80%)

Collapse Due to Economic and Bureaucratic Abstraction

The Roman Empire fell in part due to economic and bureaucratic inefficiencies. By the time of its collapse, its tax system was so convoluted that landowners abandoned their farms rather than navigate its complexity.

The Soviet Union collapsed under the weight of an over-centralized bureaucracy, where state-produced economic reports often had no connection to real production levels, leading to mass shortages.

Indigenous Knowledge Systems Keep Language Grounded in Reality

Many Indigenous cultures have languages deeply connected to the land, ensuring that words reflect actual relationships between humans and their environment.

Example: The Navajo concept of “Hózhó” represents harmony and balance, resisting the Western tendency toward rigid abstraction.

Key Takeaway: Historically, civilizations that allowed their language systems to become too abstract often suffered disconnection from reality, leading to societal failure.

Final Verdict:

✅ Language fundamentally shapes thought, perception, and decision-making.

✅ Overly abstract financial, legal, and political systems can become self-perpetuating, detached from human needs.

✅ Historical collapses often correlate with bureaucratic complexity and linguistic disconnection from reality.

✅ Indigenous knowledge systems maintain linguistic ties to lived experience, offering models of resilience.

Possible Solutions:

Simplify Legal and Financial Language – Laws and contracts should be understandable to the average citizen.

️ Ensure Political Language Reflects Reality – Avoid euphemisms that distort public understanding.

Preserve Indigenous and Holistic Knowledge Systems – They offer models for keeping language tied to reality.

Promote Critical Thinking and Linguistic Awareness – Education should teach people how language can be used to manipulate perception.

Discussions

There are no discussions yet.