We live amidst technological marvels that would have seemed like magic to past generations, yet these same technologies have birthed unprecedented levels of anxiety, alienation, and ecological destruction. The smartphone in your pocket holds more computational power than NASA used to land a man on the moon, but it also hosts algorithms designed to hijack your attention, erode your mental health, and commodify your every thought.

The central problem is not technology itself, but the assumption that every problem created by technology can be solved with more technology. When fossil fuels pollute the planet, we don’t reconsider our addiction to endless energy consumption, we invent carbon capture machines. When social media exacerbates loneliness and polarization we don’t step back to reimagine community, we design new apps.

This technological treadmill accelerates faster than our psychological, social, and ecological systems can adapt. Past civilizations collapsed not from a single catastrophic event, but from the accumulation of unsustainable practices that outpaced their ability to respond. The difference today is that if we collapse, it will be global and accelerated by interconnected technologies operating at breakneck speeds.

The agricultural revolution unfolded over millennia. The industrial revolution took centuries to reshape societies. But the digital revolution has transformed every facet of human life in less than fifty years. We are biologically the same species that once roamed the savannas, yet we are now expected to thrive in environments flooded with artificial light, infinite information, and the relentless ping of notifications. The result is cognitive overload, decision fatigue, and a fragile attention span that diminishes our capacity for deep thought and meaningful connection.

Even the most well-intentioned technologies carry unforeseen consequences. The Green Revolution of the mid-20th century dramatically increased food production through chemical fertilizers and pesticides. Hailed as a miracle, it later revealed devastating ecological costs: soil degradation, water pollution, and the collapse of local farming traditions. This pattern repeats with plastics, nuclear energy, artificial intelligence, and beyond. Each new solution spawns its own set of crises, demanding yet another tech fix in an endless feedback loop.

Studies have linked excessive technology use to rising rates of depression, anxiety, and social isolation. Jean Twenge, in iGen, documents how the generation raised on smartphones experiences unprecedented levels of mental health issues, correlating with screen time and the erosion of face-to-face interactions. The problem is not simply what technology does to us, but what it prevents us from doing: experiencing boredom, engaging in unmediated conversations, or contemplating life.

The unchecked acceleration of technological development is not just a practical problem; it is a philosophical one. We have built a world where technology dictates the pace of human life, rather than the other way around. As artificial intelligence advances, social media rewires our social instincts, and automation displaces entire industries, we are not merely adapting to new tools—we are being reshaped by them. Some technologies may be harmful, and our uncritical acceptance of every new innovation erodes our ability to say no.

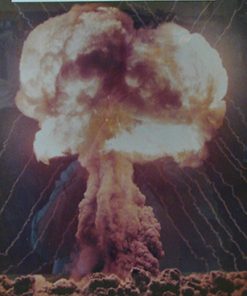

Modern societies rush to implement whatever is technically feasible without considering whether it enhances or diminishes human life. The nuclear bomb, surveillance capitalism, and the algorithmic manipulation of public opinion were not accidents—they were choices, made without restraint, now impossible to undo. The myth that technology is neutral, that its consequences depend only on how it is used, is one of the great delusions of modernity.

There are limits, not only to what we should invent, but to what we can control. The complexity of global systems is now so vast that unintended consequences multiply exponentially. Artificial intelligence systems develop biases their creators do not fully understand. Social media platforms intended to connect people instead fragment society into warring tribes. Geoengineering projects, proposed as solutions to climate change, risk disrupting delicate planetary systems in ways we cannot predict. At a certain point, humanity must accept that some things are beyond its grasp and that wisdom often lies in restraint, not escalation. If technology is to serve us, rather than enslave us, we must reclaim the ability to decide which innovations deserve a place in our lives and which should do not.

Some cultures have consciously limited technological adoption. The Amish, often caricatured as anti-modern, are selective rather than Luddite. They evaluate each new technology based on its impact on community and well-being. If a device undermines social cohesion or fosters dependence, they reject it.

A deliberate approach toward technology fosters resilience, strong communal ties, and clarity of purpose often missing in hyper-connected societies. By prioritzing stability over abstraction, many traditional cultures remained vital for millennia. Stability should be the goal, never to be equated with stagnation.

E.F. Schumacher’s concept of Intermediate Technology emphasizes human-scale, sustainable solutions that balance efficiency with accessibility. Instead of relying on high-tech, centralized systems or low-tech, labor-intensive methods, Intermediate Technology offers a middle path—affordable, low-energy, and easy-to-maintain tools that empower local communities. Examples include treadle pumps for irrigation, biogas digesters that turn waste into energy, rocket stoves for efficient cooking, and bicycle-powered machines that provide mechanical assistance without electricity. These technologies operate within natural and social limits, supporting self-sufficiency while avoiding dependence on resource-heavy industrial systems.

Technologies should be evaluated not just for efficiency or profitability, but for their ethical, psychological, and ecological consequences. If England had anticipated the logical results of the Industrial Revolution—child labor, fouled air, stressful and dangerous workplaces, squalid living conditions—much human suffering could have been avoided.

Therefore, under Folklaw:

Technological development shall be subject to rigorous ethical scrutiny, with mandatory impact assessments that consider environmental sustainability, psychological health, and social cohesion.

All new technologies must undergo a moratorium period for public review before widespread adoption. Governments will establish independent Technology Review Councils composed of ethicists, scientists, environmentalists, and community representatives to evaluate long-term consequences. Intermediate Technology alternatives shall be considered wherever possible.

Planned obsolescence shall be prohibited, and companies must design products for durability, repairability, and ecological compatibility. Public funding will prioritize technologies that restore ecological balance, support local resilience, and enhance human well-being without fostering dependency.

Discussions

There are no discussions yet.