We stand today not at the edge of one crisis, but many: ecological unraveling, spiritual drought, political exhaustion, rampant inequality. These are not separate events or isolated catastrophes converging by coincidence. They are symptoms of a deeper malady—an inherited blindness, a way of seeing the world that splits what was never separate, dissects what was once whole, and names only the parts it can measure while scorning the rest as myth or sentiment. The real crisis is one of perception.

We did not always see this way. Tribal cultures and ancient civilizations typically viewed the cosmos as a dynamic unfolding—an ever-shifting interplay between opposing yet complementary forces. Daoist philosophy named these forces Yin and Yang. These are not good and evil, nor static categories, but relative aspects of reality: shadow and light, receptivity and activity, stillness and motion, feminine and masculine. All natural systems, when in health, express a rhythmic alternation and mutual dependency between these poles. The Dao, or the Way, is the underlying harmony that emerges when these forces remain in balance—neither side dominating, neither side denied. To live in accord with the Dao is to recognize patterns of excess and restraint, and to move with the grain of the world, not against it. Many spiritual traditions echo this truth.

But some five centuries ago, in the long shadow of the plague and the birth pangs of industry, the Western mind made a terrible wager: that it could master the world by standing apart from it. That reason could slice through the living tissue of reality and emerge with truth in hand, clean and bloodless. It was an intoxicating gamble, and for a while, it worked. We split atoms. We mapped genomes. We turned forests into ledgers and rivers into engines. But the cost, long deferred, is now due. We have gained the world and lost the thread. The root of this estrangement lies in the cold certainties of the 17th century.

Francis Bacon (1561-1626) urged his peers not merely to observe nature but to wrest its secrets by force. He likened inquiry to interrogation, even torture—nature bound to the rack until she confessed. Knowledge, in this scheme, was not communion but conquest: the subjugation of a living world into a storehouse of usable facts. This shift sanctified extraction, casting curiosity as domination and experiment as a kind of sanctioned violence.

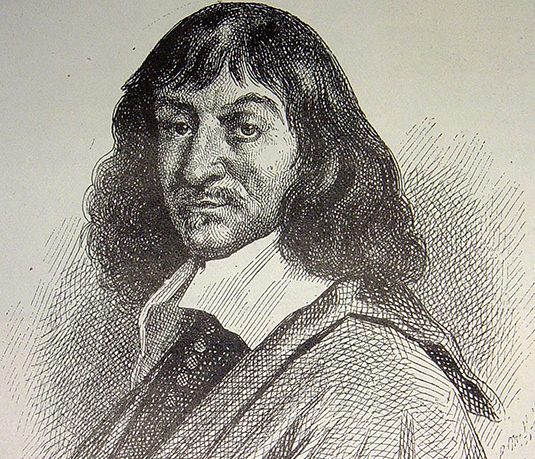

René Descartes (1596-1650) looked out upon the world and likewise saw not communion, but control. “Cogito ergo sum,” he said—I think, therefore I am. With this phrase, he carved a rift between mind and matter, subject and object. The soul became a ghost in a dead machine, and the earth—a soulless thing.

Isaac Newton (1642-1727) then carried the mechanistic worldview to its height. He invented calculus to map motion with mathematical precision, giving form to what had been only rough observation. By uniting Galileo’s studies of falling bodies with Kepler’s planetary orbits, he brought gravity into the picture, a single invisible force binding heavens and earth. The universe, under Newton’s gaze, became a perfectly tuned machine—predictable, calculable, and, in theory, entirely knowable. Newton’s calculus proved to be true in the mapping of eliptical plantetary orbits and billiard balls, even in the motion of chemicals and gasses.

Science now reimagined the cosmos as a lifeless clockwork mechanism and the human being as its rightful master. Complexity was reduced to parts, and parts to predictable functions. What began as method hardened into metaphysics. The machine metaphor—invaluable for studying levers and lenses—spread through every institution. Psychologically, the world was divided into subject and object—an observer standing apart from an inert universe, mind trapped as a ghost within the machine of matter. From this fracture came the “mind–body problem,” the riddle of how lifeless particles could ever give rise to consciousness, meaning, or will. The whole was understood by breaking down the parts. Biology saw the body as a clockwork of fluids and gears. Economics imagined people as rational cogs maximizing utility. Education became the mass production of compliant units. Politics degenerated into systems management. And all the while, the soul—of people, of places, of the planet—was written out of the script.

This mechanistic worldview became our default setting, rarely questioned even by those who sought to resist its outcomes. Marxism mirrored its industrial assumptions. Capitalism perfected them. Even modern medicine, despite its miracles, often treats the body like a malfunctioning vehicle—replace the part, suppress the symptom—while ignoring the invisible tides of context, connection, and consciousness that shape our health. This same worldview seeped into daily life as habit and common sense. We now speak of ourselves as “individuals”—a word that once meant indivisible, but now implies separation. We trust abstraction over intuition, statistics over story, efficiency over empathy. Time is no longer sacred or cyclical—it is a linear conveyor belt, chopped into hours and minutes, each to be optimized.

Yin—associated with intuition, rest, receptivity, femininity, and embeddedness—was dismissed as passive or unscientific, while Yang qualities like control, measurement, expansion, masculinity, and conquest were elevated as universal goods. The result has been a hypertrophy of Yang: growth without limit, action without reflection, assertion without listening. This imbalance has not only ravaged ecosystems and cultures, but has driven the modern psyche into exhaustion.

Most insidiously, the Cartesian split taught us to doubt what could not be measured. It colonized imagination. It created a monoculture of perception, where empirical data reigned supreme and other ways of knowing—embodied, ancestral, artistic, contemplative—were discarded as superstition or sentimentality. When Huston Smith chaired MIT’s small Philosophy department, his attempts at small talk with the technologists often fell flat. Explaining that he was concerned with quality and symbol rather than quantity and measure, one scientist replied: “So, the difference between us is that I count, and you don’t!”

The use of fossil fuels—coal, oil, and gas—marked a historic turning point. Concentrated energy now powered machines that vastly extended human capacity. Landscapes were mined, forests cut down, and soils treated as raw material for extraction. Engines, factories, and turbines became the central machinery of modern life. Fuels built up over millions of years—a one-time inheritance—are being exhausted within just a few generations of mechanization. The apex of this worldview emerged with the unleashing of nuclear force. Here was the culmination of reductionism: a science that could split matter itself, creating a technology capable of annihilating entire ecosystems in a flash. In the nuclear age, man no longer merely shaped the world—he threatened to unmake it. The Promethean bargain was fulfilled, and the gods fell silent.

And yet… cracks had already begun to form in the edifice with the development of quantum theory, systems analysis, and recursion.

“‘Descartes’.” by Biblioteca Rector Machado y Nuñez is marked with Public Domain Mark 1.0. (Cropped)